The United States aims to promote Vietnam as a semiconductor production hub, but the shortage of engineers is becoming a concern

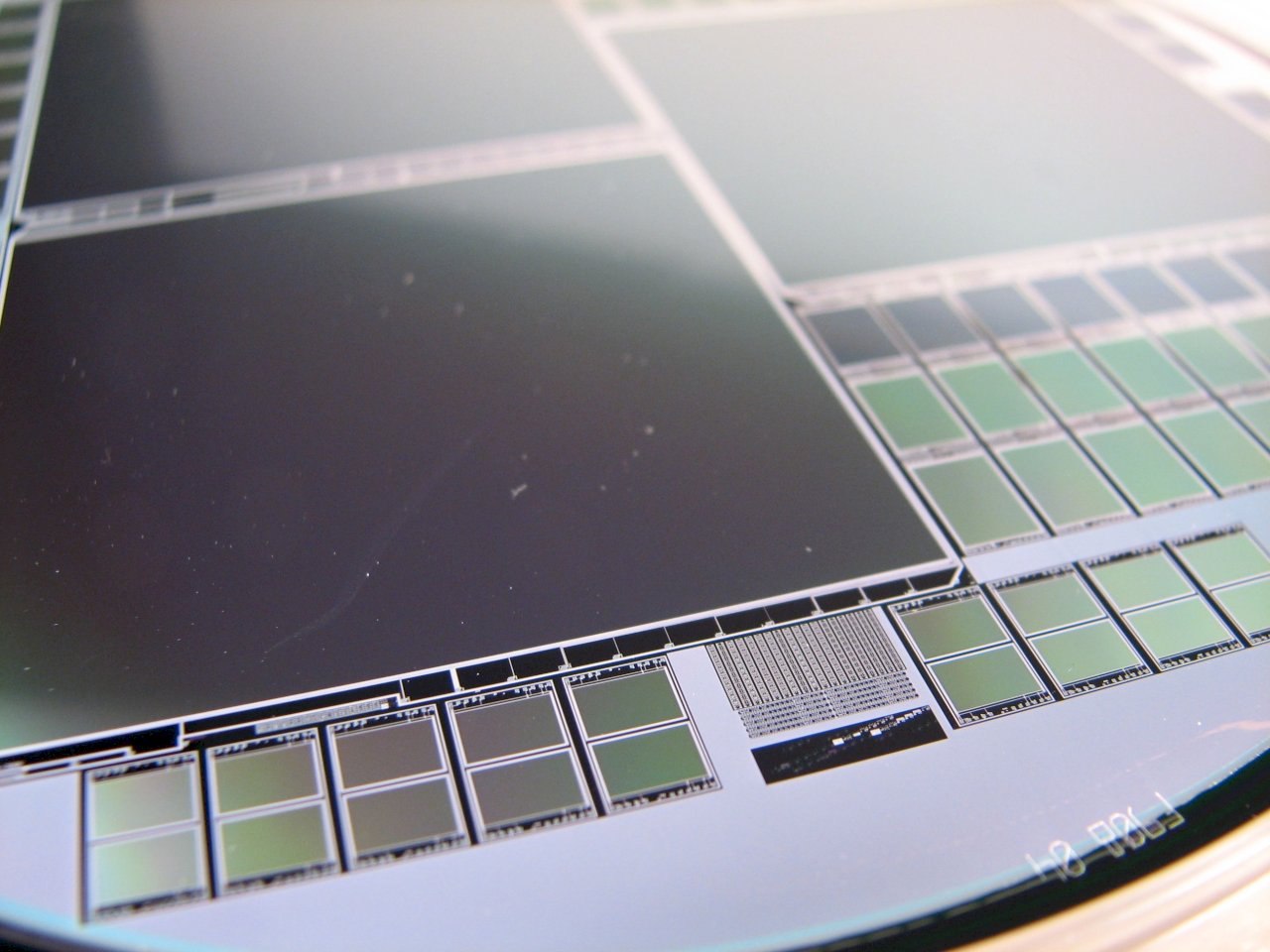

Photo (Wunderstock Gallery)

After the U.S.-China trade war, many large technology conglomerates shifted their investments to Vietnam, boosting Vietnam’s chip exports. The government of U.S. President Joe Biden is planning to support Vietnam in quickly becoming a chip supply center to mitigate supply chain risks related to China. However, Vietnam is facing a significant challenge in the long-term shortage of engineers.

The U.S. “Friend-shoring” strategy: Vietnam enjoys significant benefits

In order to concentrate supply chains within like-minded geopolitical allies, the U.S. government is actively promoting the “Friend-shoring” strategy. Due to the warming relations with the United States, Vietnam has clearly benefited from the recent semiconductor supply chain reorganization in the U.S. The United States hopes to establish Vietnam as a hub for semiconductor production, but the severe shortage of engineering talent is the biggest concern for the development of Vietnam’s semiconductor industry and a significant challenge to the U.S. plan to rapidly bolster Vietnam as a chip center to offset supply chain risks related to China.

Following the G20 summit, President Joe Biden visited Vietnam with the goal of further enhancing bilateral relations, with semiconductors expected to be a focal point. Biden is prepared to assist Vietnam in increasing semiconductor production.

The semiconductor industry holds strategic importance, and “Friend-shoring” has consistently been one of the key incentives the United States uses to persuade Vietnam’s Communist Party leaders to agree to formal relationship upgrades. Initially, Vietnam was hesitant due to concerns about potential negative reactions from China.

Talent only meets 1/10 of the demand

The enhancement of relations with the United States could bring in billions of dollars in new private investment and some public funding for Vietnam’s semiconductor industry. However, industry officials, analysts, and investors say that the severe shortage of trained engineers is likely to be a significant barrier to Vietnam’s rapid development in the chip sector.

Vu Tu Thanh, the head of the Vietnam office of the US-ASEAN Business Council, stated that “the available number of hardware engineers falls far short of what is needed to support billions of dollars in investment,” accounting for only about one-tenth of the expected demand over the next ten years.

With a population of around 100 million, Vietnam has only 5,000 to 6,000 trained hardware engineers for semiconductors, while the industry is projected to need 20,000 engineers within the next five years and 50,000 within the next decade.

Hung Nguyen, the Senior Manager of Supply Chain Projects at RMIT University Vietnam, also pointed out that Vietnam lacks semiconductor software engineers.

Regarding this issue, various Vietnamese government departments, including labor, education, information technology, science and technology, and foreign affairs, have not responded.

Expanding from Back end Manufacturing to Design

According to Vietnamese government data, Vietnam’s semiconductor industry exports to the United States are worth over $500 million annually, primarily in the backend manufacturing phase of the supply chain, which includes chip assembly, packaging, and testing. However, the industry is gradually expanding into areas like design.

The White House has not yet specified which parts of the Vietnamese semiconductor industry will be prioritized, but U.S. industry executives suggest that the backend is a crucial growth sector.

China plays a significant role in these considerations. According to data from the Boston Consulting Group, nearly 40% of global backend manufacturing was in China in 2019, with the United States accounting for only 2%, and an additional 27% in Taiwan. China’s increased military activities around Taiwan and rising tensions have raised concerns about supply chain vulnerabilities.

Intel, an American company, has been operating the world’s largest semiconductor assembly, packaging, and testing factory in Vietnam for 15 years. However, Beijing still dominates the industry. Nonetheless, during U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen’s visit to Vietnam in July, it was announced that Amkor, a U.S. company, is building “an advanced semiconductor assembly and testing mega-factory” near Hanoi.

Furthermore, more private investments may come into play, particularly if a significant portion of the $5 billion provided for the global semiconductor supply chain under the CHIPS Act ultimately finds its way to Vietnam.

Legislative and administrative coordination is no easy task, and the short-term shortage of technical talent complicates matters

According to Hong Nguyen, the United States may also be interested in increasing the supply of semiconductor raw materials from Vietnam, especially rare earths. Vietnam is estimated to have the world’s second-largest rare earth reserves, trailing only behind China.

Vietnam is also making progress in the field of semiconductor design. The U.S. semiconductor design software company Synopsys has already begun operations in Vietnam, while Marvell, a competitor, has reduced its research and development teams in China and plans to establish a “world-class” center in Vietnam.

Furthermore, Vietnam has attracted investment interest from semiconductor manufacturing equipment producers and has ambitious plans to establish its first semiconductor manufacturing fab by the end of this century.

However, if the issue of the shortage of skilled labor is not adequately addressed, Vietnam’s ambition to develop the semiconductor industry may be challenging to realize and become more vulnerable when facing regional competitors like Malaysia and India.

Intel has repeatedly urged Vietnamese authorities to expand the pool of skilled workforce.

Insiders revealed earlier this year that Intel was considering doubling its $1.5 billion business in Vietnam, but it is currently unclear whether this plan still exists after the company announced significant investments in Europe in June.

Intel has not responded to requests for comment.

On Amkor’s Vietnamese website, there are approximately 60 job openings, primarily for engineers and managers.

Vu Tu Thanh suggests that one possible workaround could be to relax regulations in Vietnam regarding work permits for foreign engineers until the domestic skilled labor force is sufficiently developed.

However, this would require legislative reforms and expedited administrative procedures, which, according to several Vietnamese diplomats and entrepreneurs, is not an easy task.

Refer to the original post here

For additional details, refer to our SIA services | Link