Is the dream of building a semiconductor industry, or specifically producing chips in Vietnam, achievable? And if it is achievable, how should Vietnam go about implementing it to avoid damage and risks?

The story of semiconductors and chips is gaining momentum in Vietnam, especially after President Joe Biden’s visit to the country and the new development directions aimed at prioritizing high-tech industries in the upcoming period. Perhaps, Vietnamese people are increasingly motivated to focus on building a chip manufacturing industry, given the context in Southeast Asia where countries like Singapore and Malaysia have established semiconductor fabrication plants, crucial for many products, including consumer electronics. But is this dream feasible for Vietnam?

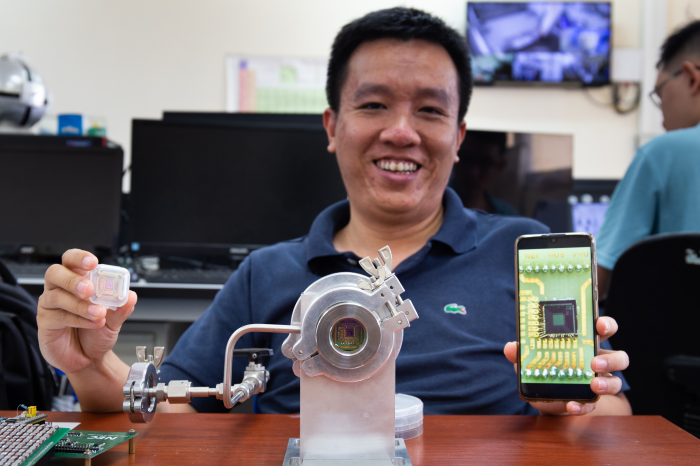

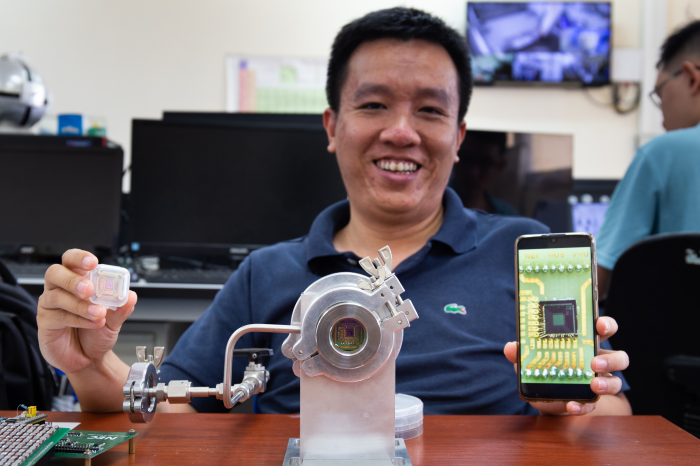

Based on observations of global semiconductor industry trends and personal experiences from conducting research and experimental chip production, Assoc. Prof. Nguyen Tran Thuat from the Nano and Energy Center at the University of Natural Sciences, Hanoi National University, believes that despite numerous challenges and uncertainties, the door to entering the chip industry remains open for Vietnam. The key issue is whether Vietnam can choose a breakthrough direction and persevere in pursuing it.

An approach to entering the chip industry for Vietnam

Question: In your opinion, given the current state of science and technology in Vietnam, can we establish a chip manufacturing industry?

Answer: Chip manufacturing is an enticing industry with an incredibly vast market. Even at present, it can be predicted that the global demand for chips will continue to rise. Virtually, we cannot live without chips, as all the devices we use in our daily lives, from phones, cameras, refrigerators, and TVs to medical equipment and citizen identification cards, all require chips. Even seemingly simple things like the power circuit in a phone charger also require power chips.

In April 2023, Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh visited and worked at Hanoi National University, ordering the development of a project for a center to support integrated circuit design, measurement, and testing, as well as a national integrated circuit manufacturing laboratory. I believe that the idea of building the chip industry has been considered and discussed among government leaders to seize the promising opportunities that this industry can bring to Vietnam.

Question: So, at this point in time, is it truly feasible for Vietnam to build a chip industry?

Answer: To answer this question, we first need to understand that the stringent requirements for every stage of chip production, from material development to the final packaging of a chip product, are significantly higher compared to many other manufacturing sectors. Even in the context of semiconductor manufacturing laboratories, the operational processes and testing must adhere to extremely strict standards. For instance, the cleanliness requirements for such laboratories far exceed those of any cleanrooms currently available in Vietnam. Imagine that each type of integrated circuit has two types of transistors, N-channel transistors and P-channel transistors. To manufacture these two transistors so they can operate without malfunction, the environment where they are created must be extremely clean and free from impurities. Once impurities are present, it’s nearly impossible to clean, and it can result in the entire production line being compromised, with no viable repair options, often necessitating a complete reset.

So, while building a chip industry is an appealing prospect, it involves significant technical and infrastructural challenges that must be carefully addressed to make it feasible for Vietnam.

The development of the chip industry also has many distinct characteristics compared to other industries; it demands a steadfast and long-term strategy and cannot be rushed. Therefore, before thinking about success, I believe we need to ensure survival first.

Assoc. Prof. Nguyen Tran Thuat

Because of its inherent nature, it demands a very meticulous, detailed, and careful approach, with a focus on the final refinement steps. This is akin to the idea that we need to exert 99% of the effort to complete the remaining 1% of the task. In some aspects, it can be seen that chip manufacturing is a highly challenging endeavor for Vietnam at present.

Question: So, should Vietnam embark on this endeavor?

Answer: Despite the challenges, why should Vietnam pursue this? Perhaps, it’s not just about a vast and promising market; chip manufacturing also offers another advantage for Vietnam in that it can create products that, if not produced locally, may not be available at all.

Some Southeast Asian countries like Singapore and Malaysia have semiconductor fabrication plants, while Vietnam currently does not. In my opinion, Vietnam can still achieve this if it selects a good direction and perseveres. This narrative has also begun to emerge in Vietnam, for instance, with FPT Semiconductor already making strides. Hopefully, they will gradually venture into computational chips like ARM or graphics chips and digital memory chips. FPT Semiconductor’s approach, like that of all other chip-related companies in Vietnam, involves designing the chips themselves and then outsourcing the fabrication and packaging.

Question: Is this the approach that companies around the world typically follow?

Answer: When looking at the development history of major chip manufacturers worldwide, their development directions can be broadly categorized into three:

1. The strongest approach is exemplified by Intel, which designs, manufactures, packages, and sells products directly to the market.

2. The second type is fabless, which focuses solely on design, as seen in companies like Nvidia, Qualcomm, Broadcom, and others. These companies either outsource the design or do it in-house, then subcontract fabrication, including system-on-chip (SoC) solutions, and packaging. They also provide operating system support, software support, and various hardware components for chip purchasers.

3. The third category is pureplay, represented by companies like TSMC and UMC in Taiwan, which concentrate solely on manufacturing without involvement in other stages, including design.

Of course, the shaping of these development directions is influenced by historical factors as well. For instance, in the past, AMD was a direct competitor to Intel, but over time, AMD stopped manufacturing (spinning off its production division into Global Foundries) for various reasons, including the fact that Samsung and TSMC had already excelled in this aspect. The semiconductor industry’s distinctive feature is that it demands a significant amount of know-how, both in design and in manufacturing (tapeout) prototypes. Therefore, if a place can handle all stages to produce the final product, it is both challenging and costly.

Question: So, what can Vietnam learn from them to follow one of these three directions or shape a new one?

Answer: In my opinion, for a country like Vietnam, devising a completely new fourth development direction is a challenge because no country in the world has achieved this yet. So, in the pursuit of developing the chip industry, what direction can Vietnam take? I believe there’s a model that some places apply, known as “fablite,” which means manufacturing a part of the chip rather than the entire chip from A to Z. If Vietnam chooses this path, it will focus on specific types of chips rather than trying to produce all types. This approach can be effective because if Vietnam were to dive into manufacturing chips like computer logic chips and memory chips, it would be extremely challenging to compete effectively.

The reason why it’s possible to participate in manufacturing a portion of certain chips is because, after the chip’s circuit design is completed, there are many layers on the chip, each with a specific geometric shape. These shapes are created using specialized machines, for example, those from ASML (Netherlands), and then the next step is shaping the required materials. Chip production typically involves dozens to hundreds of steps to match the chip’s function, whether it’s an analog chip, logic chip, or memory chip. However, for some specialized types of chips, it’s possible to manufacture the circuitry on a wafer abroad and then continue the remaining steps in Vietnam on that wafer. This step is referred to as “post CMOS” (Complementary Metal Oxide Semiconductor) in the chip manufacturing industry, and it’s used to produce various types of chips (such as image chips, microelectromechanical system (MEMS) chips, sensor chips, etc.) on the processing unit, control unit, static RAM, and other logic gates.

Question: Do you believe that if Vietnam intends to develop in this direction, Vietnam will do well?

Answer: I think it’s possible. Typically, the chip manufacturing process is divided into multiple stages. The first stage (front end of line) is very delicate in terms of size and also involves heat, the second stage (back end of line) is used to manufacture simpler and larger components, and then depending on the type of chip, there’s the final stage (post CMOS). If we excel in the third stage, we can progress to the second stage. Of course, in the global chip manufacturing industry, no one completes the first stage and then creates conditions for the next stage to be done elsewhere. However, the reverse is possible; the second stage can help us produce certain types of chips that the first stage can potentially replace with simpler processes.

When Vietnam develops with a focus on in-house design and packaging, there is an opportunity to gradually transition from partial manufacturing (fablite) towards full-fledged manufacturing (full fab). If Vietnam wants to move towards chip manufacturing, I think it may have to follow that path.

Vietnam’s preparatory steps

Question: In the case of choosing this development direction, what advantages does Vietnam have?

Answer: I believe Vietnam does have certain advantages. Firstly, Vietnam has already made strides in the semiconductor industry. Achievements like those of FPT Semiconductor are excellent examples. In terms of output, they have secured stable orders for the chips they produce. Regarding capabilities, they started by outsourcing design work, gradually improving their design process, and then moving on to outsourcing manufacturing. This approach ensures a certain source of income and enables them to develop different types of products.

Secondly, in Vietnam, the workforce for chip design is beginning to develop, both in academic and professional environments. Currently, some chip companies in Vietnam are adopting the same approach as FPT Semiconductor. If Vietnam chooses the fabless path with packaging as the main focus, there should be a focus on training chip design engineers who can create designs and then outsource manufacturing.

Question: So, do foreign direct investment (FDI) companies establishing manufacturing plants in Vietnam provide some advantages to support the development of our chip industry?

Answer: Typically, foreign companies set up factories in Vietnam to utilize the local workforce for tasks they don’t consider core technology, meaning they need to incorporate some additional details into their products. In such cases, they may positively impact Vietnam by allowing Vietnamese engineers to divide the work, with each side handling different components that are then assembled into a larger product. This way, the local workforce can still accumulate expertise and experience in chip manufacturing.

In the event that we develop along the fabless path, meaning we only focus on design and outsource manufacturing, we would primarily need a workforce skilled in IC design, as well as those trained in electronics engineering and embedded software development. As for the workforce capable of handling the packaging process, we would need technicians.

For Vietnam, preparing a workforce with these skills is much more effective than investing in a chip manufacturing infrastructure. Investing in such a manner would require consideration of various associated processes that need tight control, which not only increases investment costs but also requires at least four additional types of engineers to operate such a chip manufacturing facility.

I believe that preparing the workforce in the design field as described is suitable for Vietnam’s conditions. Clearly, it will be effective because being involved in circuit design doesn’t mean we can’t understand other processes. Skilled designers may even contribute to process improvements and develop new manufacturing processes.

Question: How do you assess Vietnam’s current workforce?

Answer: Vietnam currently has a certain number of electrical engineers, electronics engineers, software engineers, and IC design engineers. However, there is a significant shortage of engineers involved in the chip manufacturing process because there are very few educational institutions in Vietnam that offer programs to train process engineers.

Here, the issue is not that educational institutions are not responsive enough to open process engineering training programs; the problem is that if there is demand, universities will immediately plan to meet it. This is still a supply and demand problem, where education responds to workforce needs rather than training in anticipation of demand. For example, aviation programs attracted attention from society because Vietnam Airlines announced that they would hire engineers immediately after completing their training. Ultimately, a training program without demand from businesses or society is challenging to garner the interest of families whose children are considering career choices. Therefore, in the initial stages, state incentives and encouragement play a crucial role in developing the workforce. These incentives, at the very least, instill initial confidence in training institutions.

Question: Does this mean that the development of the semiconductor industry will depend heavily on the government’s direction?

Answer: If the government provides clear guidance and a well-defined roadmap for the development of the semiconductor industry, I believe Vietnam can develop as expected. On the other hand, the development of the semiconductor industry has many differences compared to other industries; it requires a firm and long-term strategy and cannot be rushed. Before thinking about success, I believe survival is the first challenge. Producing a prototype chip is already a daunting task, and selling chips is even more challenging. Therefore, it may take 15-20 years before we can truly understand what lies ahead. For example, a large French company took about 40 years to achieve success, with the first 20 years being a period when no one believed the company would survive, and it took another 20 years to become the world’s second-largest semiconductor company.

Thank you for the exchange and sharing.

Reference to our one-stop services for Taiwanese businesses | Link

Meet our consultants